Fiasco: Putting Up Hay

I brush Mrs. Horse and listen to Martin Shaw say we might entertain angels

Fiasco. Every year Bruce mutters fiasco. “But it works out,” I say. I remember the time a storm sped down from Minnesota soaking raked rows of hay—500 bales worth. But even then, a neighbor round baled it for his cattle. Often, we haven’t known who would help put it up, but someone invariably arrives to move those bales onto the wagon, off the wagon and into the sweaty, dusty loft.

Make hay when the sun shines, speaks truth for grass farmers, who harvest the sun, when we cut, rake and bale our fields. But it’s hard to find three or four dry days when forecasters call for rain, and it stays dry, or they call for sun and it rains on cured hay.

Wet hay heats up and molds. It can burn your barn or wreck your lungs. Our region has ached for rain. The air shouts for joy as it falls. The baby crops lift their stems, growing leaves, sinking roots, drinking.

I switch my prayers for rain to prayers for sunny days because this year we cut part of the field, not wanting to risk the whole thing, because forecasters called for rain that never arrived.

Meadow birds and lightning bugs enjoy extra time with the tall grasses. Honeybees nurse the red clover. Redwing blackbirds and grackles flirt with me, landing on the electric wires chirping. I wish them good morning and offer apologies for when we drop the field.

I’m Katie Andraski and that’s my perspective.

This aired on Monday on WNIJ, but has not been posted on their website. Apologies.

Sunday, June 22

While I listened to Martin Shaw’s essay Alchemy is the Sister of Prophecy I carried some flakes of hay to Mrs Horse, but as I dumped it into her bucket, I sniffed mold. This mold hides so deep I don't see it and sniffing it is probably one of the most dangerous things I do. A CT scan showed I have the early stages interstitial lung disease which can be caused by hay mold or mixed connective tissue disease. Mayo Clinic describes it this way, “Most of these conditions cause inflammation and progressive scarring of lung tissue. As part of this process, lung tissue thickens and stiffens, making it hard for the lungs to expand and fill with air.” I have passed all my breathing tests and several CT scans across several years have shown the banding is stable. I think my rheumatologist treating the mixed connective tissue disease saved my hide and my lungs.

I took the flake back to the barn and picked out better flakes from another bale. We have burned many bales this year because of mold and were running out of hay to feed. Last year our hay guy packed the bales so tight and heavy they couldn’t breathe. He used a huge rake rolling two rows together so the hay didn’t dry after it was raked because there was too much of it. The hay could have used another day to dry. We are lucky the barn didn’t burn. Mrs. Horse cannot have grass.

Every Sunday morning as I walk out to do chores, I listen to Martin Shaw’s The House of Beasts and Vines, then come inside and write a comment because there is enough spark to draw my words. On this Sunday, the second Sunday our hay is lying quietly and sweetly on the ground. I walk outside to air as close and wet as a bathtub. I’ve walked the dog a short walk, watching how she is panting and turn toward home early. I take a long breath inside and watch her flop on the tile floor.

While I listened to Shaw’s “We are a Song Being Sung Elsewhere” my husband Bruce finished pouring water into the buckets. I gave him a smooch. In the barn I squeezed some ointment into Mrs. Horse's eyes. The flies in the night bother her before I can put on her mask. It's going to be a roaring hot day, but there is a blessed wind which keeps the air bearable and will continue to dry our hay that is thick and green, though it was dropped on Friday.

Shaw’s voice sounds like how wood would sound if it spoke. He quotes James Hillman, “I know I am not composed of sulphur and salt, buried in horse dung, putrefying and congealing, turning white or green or yellow, encircled by a tail-biting serpent, rising on wing.”

I pick up Mrs. Horse’s curry, and touch something dead and black with tiny feathers tucked under the handle. I pitch the dead into the yard and scrape ag lime over it with my foot. Then walk to the house, Mrs. Horse waiting for her morning scratch and breakfast. I pour the hose over it, dish soap and scrub it with a paper towel. I put on my gloves.

Could this be comeuppance for flushing a bug down the toilet last night? The thing wanted to live, but its struggle would not free it, the water sending it through pipes into a fetid septic tank. We let a baby bird die who was too naked for us to tend. I left a dead bird by the roadside for the buzzards that never came. (I found a label for Tom Cat rat poison by the neighbors after the garbage had been by). Lord have mercy on me a sinner.

Shaw says he sees a woman, her face painted white, shake a tin for some coins, who then disappeared down the alley. He says, “She was just the kind of person who would be making a bee line for Jesus. He never neglects to address the Underworld of his times, the leprosy of his times, the dementedness of his times. I’m not sure I can always say the same.”

Shaw notes that in twenty-five years he will be 70, then corrects, 80. And I startle since I am nearly 70. It’s hard to think I’m nearly old enough to be his mother. Hard to think what kind of children Bruce and I might have had, what our conflicts might be, what kinds of stories they might tell.

Mrs. Horse has come in the barn for a drink of water and some hay cubes. She does not like this new hay because it is first cutting—more stalks than grass. Some looks like straw. But Dr. Kevin says this is the best kind for a fat horse. I bend over with a hoof pick to check for any dirt in the crevices by the V shaped frog. Then I take her leggings and wrap them around each leg below her knees, pressing the Velcro together.

With the curry I scrub the hollow of her back with hard strokes--back and forth, back and forth—because she cannot reach this when she rolls. Mrs. Horse stretches her neck out and curls her lip. I reach under her belly and curry back and forth, back and forth.

Shaw surprises me by saying we might be teaching our angels a thing or two. He says, “James Hillman couldn’t stand the notion that we grew enlightened for our own good and loved Corbin’s claim that we did it for the enlightening of our own angel.” A few sentences later, Shaw says, “The ancient Celts believed that our lives are the myths that faery tell round the fire each night.”

I sweep the brush over Mrs. Horse’s hide, flicking away the tiny hairs that state her winter coat has begun to grow. At Solstice she does this. I wonder what kind of story would the faeries would speak of me? How am I teaching my angel? Are we surrounded by the strange whirring creatures Ezekial saw with four faces and eyes all around but we just don’t see them? Are the redwing blackbirds covers, not for the CIA like the Birds-Aren’t-Real folks but for angels, watching from electric poles?

I spray her with fly spray to keep her legs still, so she’s not slamming her hooves against the ground all day. It’s amazing how a horse can feel a fly lite on their skin.

I try to hang the buckets Bruce has so kindly filled, but Mrs. Horse sticks her head in one and pushes it to the floor so she can take a good long slurp. In a voice kinder than the breeze pushing through the barn, Shaw speaks, “So many of us are terrifically lonely, not just for conversation, or a hug, or the wag of a Boston terrier’s tail, or the breeze through barley, but for the God-contact that lives within all of those things. This is the most profound, invasive kind of Fall, and gives rise to all kinds of despair and devilment. This is where Kingsnorth’s Machine gets its purchase. Be banished! and let the Ancient Good back in. A twenty-minute walk at dusk with eyes wide may be a start. Get Blaked.”

Blaked as in William Blake the crazy mystic poet who wrote, “Tyger Tyger burning bright in the forests of the night.” We got Blaked all right when it was time to put up hay that evening, with enough sweat to stick our shirts to our backs and make us mistake dust motes for messengers from God.

Picking Up Hay 2025

Fiasco. This hay season was almost another one. First Bruce told our neighbor, the new hay guy, only to do part of the field when we had enough open days to pick up the whole thing. It was all I could do not to whisper Fiasco in Bruce’s ears.

While I was doing evening chores, I heard the sound of a motor that sounded like Bruce with the lawn mower. Nope, our neighbors had started raking the field, which means they are about to bale it. Bruce made salad and the pork chops were on the grill. I walked out when our neighbor’s wife brought the rake close to our yard.

“Do we need to need to get out the elevator?” I shouted over the sound of her antique tractor.

“Yes,” she shouted back.

Our neighbors antique tractors leaves them sitting in the heat and sun. They use an old side rake which rolls the hay into rows that aren’t so thick that it doesn’t dry.

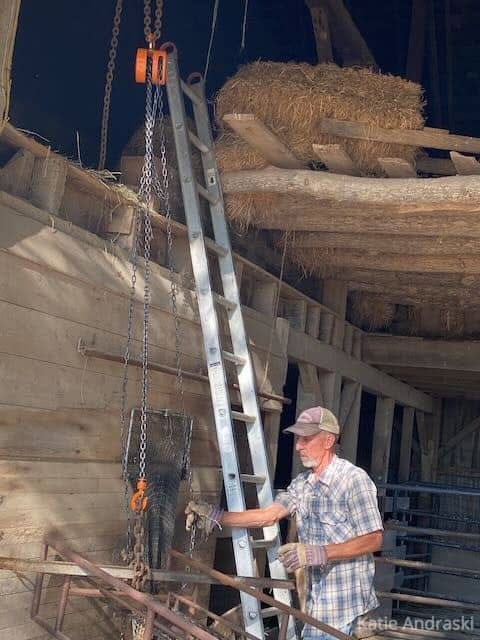

Bruce didn’t say it but his body stated, “Fiasco,” as we pulled the elevator out of the shed. It is one heavy sucker. Bruce climbed to the loft and hung a pulley system he uses to hoist the elevator so its end matches the loft floor and the bales could trundle up to whoever was stacking the bales in the hot barn. We have to take apart the paddock gates so the tractor and wagon can get into the yard. Bruce’s open shirt makes him look like he’s just gotten out of a concentration camp, and I worry that he could end up in the ER bleeding, like his doc warned about someone nearly bleeding to death five weeks after a similar surgery.

Our neighbors left the stacked wagon and disappeared, so we hitched it to the tractor and drove it to the barn. Then we saw the tire was flat. When our neighbor returned, he connected a tank to the tire and inflated it.

“It took a minute to put pressure in the tank. We’d gone home to get it.” The tank filled the tire right quick. He stood up and asked, “Could we wait until tomorrow to put it in the barn?”

He and his wife were soaked with sweat. “We were going to store it in our shed.”

“We can’t leave the elevator up because that’s where we keep the horse and it is not an easy task to put it up there and being a horse, she might hurt herself.” I sighed.

So his wife threw bales to me. I set them on the elevator, to send to Bruce and our neighbor and their son stacking them in the barn. We now have a little over 200 bales in the barn. We will take the final 100 at the second cutting. Since we are in a drought and our hay is safe in the barn, I’m going to start praying for rain again. The next day they came back and raked and round baled the rest. I was pleased the field yielded a little more than five hundred bales.

love your posts and bio katie. thanks for reposting mine.

i like bucking hay, old horses and australian shepherds too. glad we’re friends.